How are we to put a finger on our present time? It seems as though Sri Lanka is hungry and in a hurry to be fed. A frenzied cultivating of car horns, enterprise and culture; the surging of new economies, market shares and highways. A future differed is revealing itself in an ahistorical outpouring: a country in a new-found state of aspiration. Perhaps this aspiration has always been there, but this time it feels real; it feels attainable. Tomorrow is now and it is unfolding before our eyes. Whether it’s westoxification[1] or the unveiling of a new Sri Lanka to the world, something is afoot. But in all this buzz, I am curious: how will we remember this moment? Is it even worth remembering a path, if a much grander future awaits?

Enter Abdul Halik Azeez and Raki Nikahetiya, two documentarians, carving out a place in history for the noise of our present moment to be considered. They help reconfigure the question of history and the ahistorical landscape unfolding before us. They ask instead, what or who is not visible here? What or who is being left behind? Then they push further: What lies between the binaries of visible and invisible, the layered histories of those ahead and those left behind. Perhaps this line of questioning leads to a more terrifyingly cavernous question: Who are we?

I sat down with Halik and Raki to talk about their work. What follow is a collection of my thoughts on Coast and Concrete, the co-conspirators behind it, and their process of documentary.

“To approach the Other in conversation is to welcome his expression, in which at each instant he overflows the idea a thought would carry away from it. It is therefore to receive from the Other beyond the capacity of the I, which means exactly: to have the idea of infinity. But it also means: to be taught.”[2]

In his 1969 seminal essay ‘Totality and Infinity’ philosopher Emmanuel Levinas explores the relationship between terms that he defines as the self and the wholly other. He speculates about the first point of meeting where ‘the self’ previously knowing only its own constructed world encounters the stranger. In this experience, the self is transformed, and is made aware of a whole world outside of its own; Masters of Our Southern Seas by Raki Nikahetiya embodies this experience with infinite possibilities. Born in Sri Lanka in 1983, Raki and his parents left the country during times of unrest. They moved to Austria, and for Raki “reality ruptured between two poles”. He was a stranger to the land he had left, and a stranger in the land he now inhabited. This stranger-ness carries over to the way he positions himself as a documentarian. He has no illusions of tropical romanticism with which the camera has often been turned to document rural communities in Sri Lanka. Instead, ‘otherness” is always explicit in his works. His choice of black and white photography dispels any pervious association with the Sea. It suddenly becomes a foreign liquid substance that holds haunting uncertainties; a substance that the fishermen of Tallala Bay venture into daily. The assumed synonymous relationship between man and sea reveals itself to be an unfamiliar and precarious one. The ocean becomes the host to strangers that push their bodies and boats for the sake of their livelihoods. This provokes the question of, will the host accept the stranger today? The same question can be asked of the relationship between the documentarian and the community he worked for. Intentionally locating it as, “worked for” because Raki’s process can be understood as a performative exchange of labor over an attempt at advocacy.

Before he even considers bringing out his camera, Raki shows up early every morning to help move the boats. He reflects on this, as an ethical decision, a means to get involved in his subject’s life and to know some part of them before his pictures can speak of them. Yet I find myself particularly drawn to the exchange of labour that transpired. Is this exchange of labour a valid means of navigating between exploitation and exploration? Or is it simply that his willingness to labour finds him favour with the men? Either way Raki becomes part of the work in an unprecedented manner. First taken with some suspicion, but later accepted, Raki’s labour facilitates the “receiving of the other, beyond the capacity of I.”

Masters of Our Southern Seas possesses a sense of linearity. The photographs begin with a distance. The men have their backs turned to the voyeur, as they pull their nets out of the water, or push their boat into it. Raki is an intruder; a stranger to a new world. Then suddenly, he is in the boat, face to face with the men; he is less of a stranger now. The physicality of the men confronts me, and I cannot see them as an essential component of a vast industrial ecosystem anymore. I see the chaos of the sea in their bodies; the precarious balance of wood against water in their eyes. Then as quickly as it began, I retreat as Raki does, out of the boat and out of the water and away from the beach. Masters of Our Southern Seas is an exercise in stranger-ness.

Raki’s personal journey is very much intertwined with this documentary. Around the time his family left Sri Lanka, these people were part of a big pond of strangers he was advised not to draw from. Re-approaching these men as a type of stranger himself becomes a revolutionary act. Here the conditions that historically categorized some in Sri Lanka as the other are usurped. The documentarian seizes to be a mere observer, embedded deeply in the work.

Raki’s last interaction with the men, involved answering their questions on how to build a web presence to make their bed stays more lucrative and attractive to tourists. The former stranger becomes a stranger again. This might be one of the most telling moments of the sensitivities present in Raki’s work. Where they have, either been forgotten or championed in an agenda that confuses nostalgia for advocacy, these communities are caught in a paradox of conditions. They want a different life, they want change, but are caught in a “can’t live with, can’t live without” situation. Where is my place in all of this? Where do those of us, who go about “loudly knowing what’s best” put our carefully packaged opinions, solutions, nostalgias and apathies in the face of such inconvenient narratives?

Upon reading the joint artist text I expected, and must admit was sympathetic to, some neatly partisan narratives. But Abdul Halik Azeez’s work, much like Raki’s, does not indulge me in that privilege. Their work lives in the in-between.

Halik’s approach to documenting is reminiscent to the work of Colombian artist, Doris Salcedo.

Salcedo dwells on the violent history of her nation, not by showing the bodies of victims, but rather by the “traces they have left on domestic furniture and…discarded clothing.”[3] In her series Atrabiliarios Salcedo featured the shoes of the female desparecidos (the disappeared) as a means of remembering those that were held captive, abused and executed in Colombia. Salcedo was “thinking of the impossibility of burying loved ones, of elaborating mourning.” By circumventing portrayal of the victims, themselves, Salcedo charts a profound way of acknowledging their presence in their absence. Similar to Salcedo, Halik navigates social, political and historical power dynamics through a kind of erasure. Sub Urban Poetry centers space and objects as their primary focus, often relegating humans to a blur, an ephemeral presence, or sometimes even an absence in the pictorial plane. Where Salcedo responds explicitly to remembrance and violence, Halik’s street photography implies more of a sociology. By providing object and space as the primary context, Halik incites me to participate and project my associations onto the elements I see.

What is my relationship to the “political poster, fraying, on a wall?” What do I associate with the hanging shoes for sale? Do they conjure up pleasant emotions, fraught memories, or are they dismissible to me? By inviting my participation in this manner, I am given the opportunity to reflect on my reactions to the various symbols present and subsequently learn from what that interaction tells me about myself and the way in which I engage the world.

“It seems to me that the real political task in a society such as ours is to criticize the workings of institutions, which appear to be both neutral and independent; to criticize and attack them in such a manner that the political violence which has always exercised itself obscurely through them will be unmasked, so that one can fight against them.”

– Michel Foucault

It is this unmasking in Halik’s photography that makes his documentary compelling. Halik’s work looks “at micro signifiers that explain macro aspects of the social, geographic and political landscape of the city.” By, giving it a frame, a space in time and de-contextualizing these everyday scenes, Sub-Urban Poetry makes the familiar unfamiliar exposing the hidden relationships and meanings transpiring between people, places and objects.

Halik is also interested is in the “position-ality” of himself as a documentarian. The intersection of ethics, activism and exploitation is something that he is perpetually reevaluating in his work. In the case of Sub-Urban poetry, it was in understanding that he was not a neutral figure. Much like Raki Nikahetiya being inextricably embedded as a stranger in his work, Halik too acknowledges his imprint. “You are always going to project onto your subject”. When it comes to the political or sociological nature of Halik’s photographs he is adamant that you “can’t remove your own power from the conversation.” But does this embedding detract from the experience of the work? Quite to the contrary, Halik’s meaning–making projections onto to the scenes he captures, are the very reasons for their existence. It provides me with a starting point to agree or disagree, to see what Halik see’s or see something drastically different. It is precisely the potential differences of personal associations attributed to Halik’s work that speak profoundly to this contemporary Sri Lankan moment. It speaks to our dissonance and our harmony in trying to make sense of the power relations that mold and shape us.

Before the preparation for this show Halik and Raki had never met. Conceptualized and organized from different parts of the world, Coast and Concrete is a product of numerous emails, phone calls and Facebook chats. As ironic as that may seem, given the themes tackled in the show, it would be a loss to write it all off as only irony. It is far more exciting to see it as navigation through the paradox of globalization. It is precisely in this sort of a paradox that Coast and Concrete finds its most comfortable resting place. The works don’t operate in polarities alone. Instead they invite all the little complexities and impossibilities of our world to make themselves known, in stories of people, of places, of systems.

Coast and Concrete brings together the rural and the urban, the people and the context to point out the visible and unveil the invisible. I am reminded of Robert Frank and his iconic body of work titled “The Americans”. Writing about him in the New York Times Nicholas Dawidoff writes, “he recognized us before we recognized ourselves.”[4] This show does the same. It involves two documentarians in their attempt to define our public moment, to cultivate historical data, to compile, to remember.

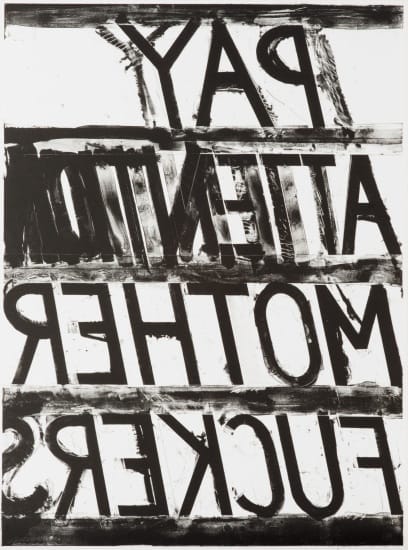

As Sri Lanka gets noisier, the temptation to find avenues of escape looms. This exhibition is that noise reframed. Coast and Concrete, is thus an example of Art in service. The service rendered: a call for us to see and question our world. For me, the 1973 Bruce Nauman Lithograph with Black letters printed backwards on a white background, functions as a great symbolic summary of Coast and Concrete. Those words, relevant even now, read as follows, “Pay Attention Motherf*****s.”

[1] Salcedo, Doris, et al. “Silence Seen, Nancy Princenthal.” Doris Salcedo, Phaidon Press, 2008.

[2] E. Levinas, ”Totality and Infinity”; trans. Alphonso Lingis, The Hague/Boston/ London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers & Duqesne University Press, 1969; 2nd edition, 1979; Springer, 1980.

[3] 1The Term was used in Mistaken Identity by the Sociologist Dipankar Gupta, who borrowed it from the Iranian intellectual Jalal-el-Ahmad

[4] Dawidoff, Nicholas. “The Man Who Saw America.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 July 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/magazine/robert-franks-america.html.

– Essay by Sandev Handy